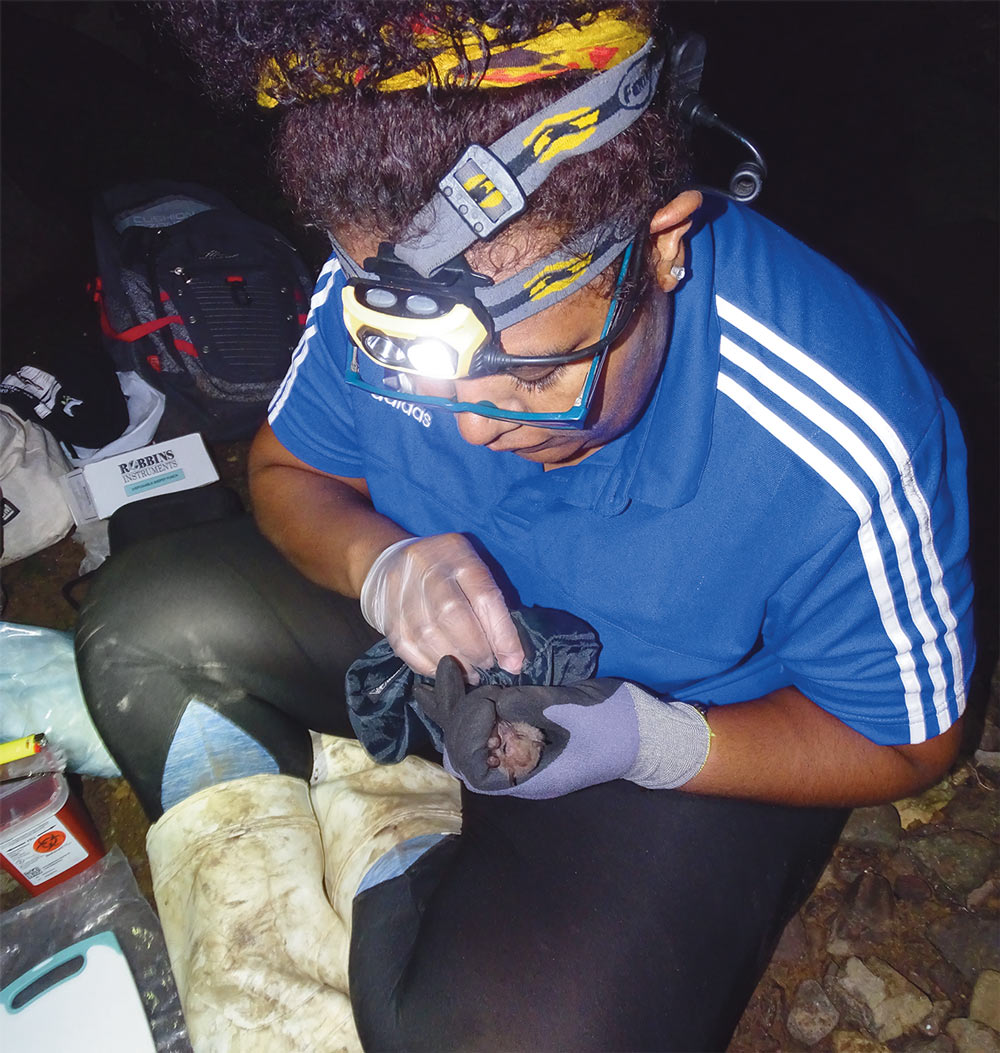

Saving the Fijian Free-tailed Bat

When the pandemic hit, Tikoca found herself stuck in South Australia, where she is working on her doctorate degree at the University of Adelaide. During this time, she coordinated more Zoom calls than she can count, all while preparing to return to her homeland of Fiji to resume her field work as soon as she could.

Fijian free-tailed bats have been observed on both the Vanua Levu and Taveuni islands, but nowhere else on Fiji’s hundreds of islands. The bats have been seen foraging in the forest canopy, in coastal habitats, and along the edge of cloud forests. The IUCN first listed this species as Endangered in 2008, with estimates of only 5,000 to 8,000 Fijian free-tailed bats remaining.

—Siteri Tikoca

This summer, Tikoca will be engaging with the stakeholders she worked with on Zoom calls: landowners, government officials, and NGO partners. She will also be compiling a database of audio files and tissue samples of bats from the varied locations to better assess and document how Fijian free-tailed bats interact with their habitats.

“We know the bats are flying between locations and across water,” Tikoca says. “My goal is to better understand the connectivity of subpopulations. We can’t rule out the possibility of new caves this species may be using—caves we don’t know about yet, caves we might need to manage.”