Bat Conservation International Bats Magazine

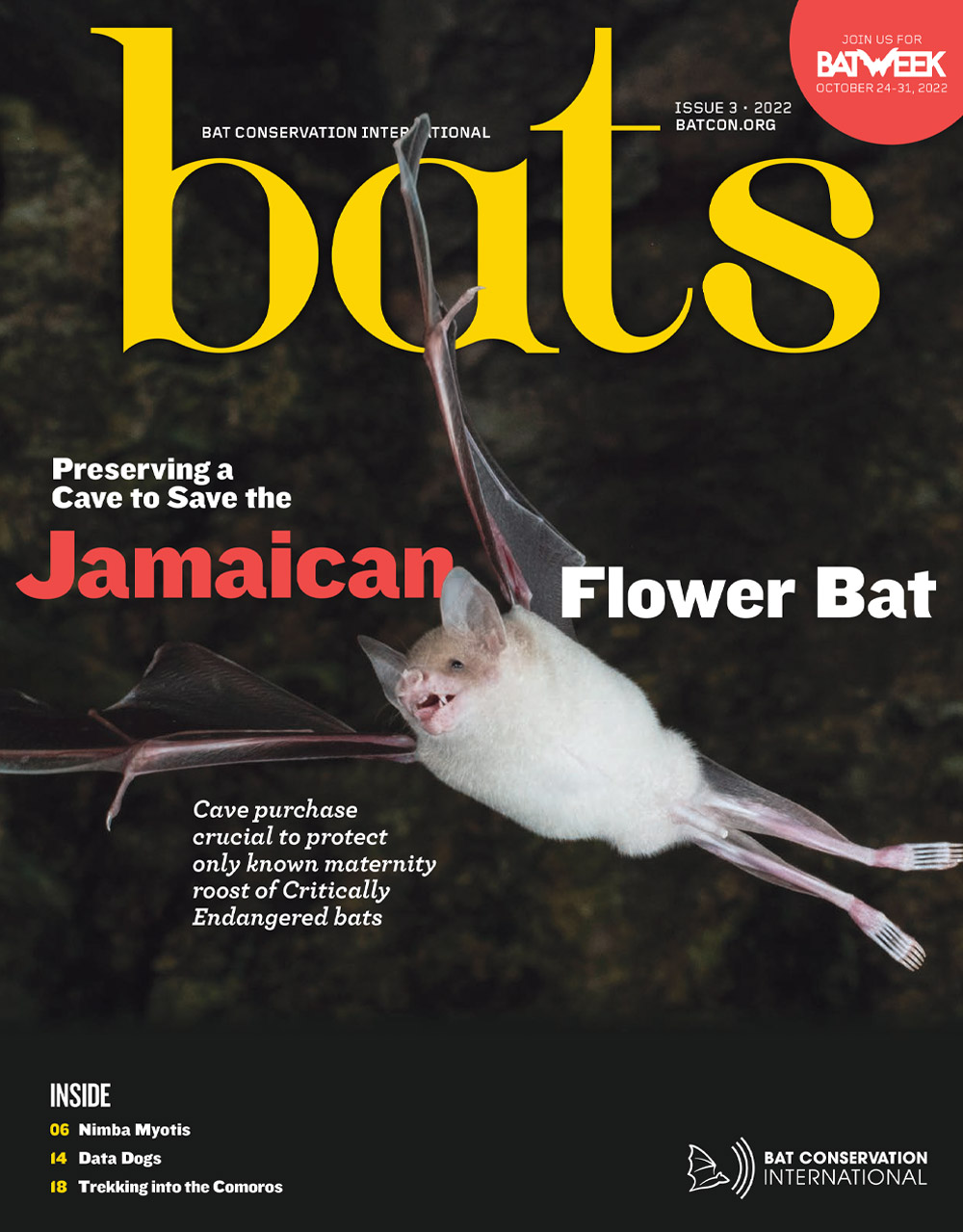

Flower Bat

Inside this Issue

Features

08preserving a cave to save the jamaican flower bat

Departments

news & updates

- Florida bonneted bat threatened by water park proposal

- White-nose Syndrome spreads

- New virtual bat experiences

- Celebrate Bat Week

- Searching for Livingstone’s fruit bats

- Bat scientists unite

- Gardening for bats

- Water loss affecting southwestern U.S. bats

Image: Sherri and Brock Fenton

Protecting Endangered Species

ecently, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) proposed to protect the tricolored bat (Perimyotis subflavus) as an Endangered species. Bat Conservation International (BCI) fully supports using the full power of the Endangered Species Act to protect the tricolored bat.

Bat Conservation International (BCI) is a 501(c)(3) organization dedicated to protecting bats and their essential habitats around the world. A copy of our current financial statement and registration filed by the organization may be obtained by contacting our office in Austin, Texas, below, or by visiting batcon.org.

500 North Capital

of Texas Highway,

Building 1

Austin, TX 78746

512.327.9721

1012 14th Street,

NW Suite 905

Washington, D.C. 20005

512.327.9721

Kristen Pope

Javier Folgar

Michelle Donahue / Proofreader

Publication Management GLC, part of SPM Group

Bats Magazine welcomes queries from writers. Send your article proposal in a brief outline form and a description of any photos, charts, or other graphics to the Editor at pubs@batcon.org.

Members: We welcome your feedback. Please send letters to the Editor to pubs@batcon.org. Changes of address may be sent to members@batcon.org or to BCI at our Austin, Texas, address above. Please allow four weeks for the change of address to take effect.

Chair

Dr. Andrew Sansom,

Vice Chair

Don Kendall, Treasurer

Eileen Arbues, Secretary

Dr. Gerald Carter

Gary Dreyzin

Dr. Brock Fenton

Timo Hixon

Maria Mathis

Dr. Shahroukh Mistry

Sandy Read

Dr. Nancy Simmons

Jenn Stephens

Roger Still

Dr. Enrico Bernard

Dr. Sara Bumrungsri

Dr. Gerald Carter

Dr. Liliana Dávalos

Dr. Brock Fenton

Dr. Tigga Kingston

Dr. Stuart Parsons

Dr. Paul Racey

Dr. Danilo Russo

Dr. Nancy Simmons

Dr. Paul Webala

Mike Daulton, Executive Director

Mylea Bayless, Chief of Strategic Partnerships

Dr. Winifred Frick, Chief Scientist

Michael Nakamoto, Chief Operations Officer

Kevin Pierson, Chief of Conservation and Global Strategy

Visit BCI’s website at batcon.org and the following social media sites:

Fight to Save the Florida Bonneted Bat Takes a Turn

In August, Bat Conservation International and conservation partners filed notice to the National Park Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for not performing the proper regulatory reviews before the National Park Service released this piece of land to Miami-Dade County to lease out to the water park development.

batsignals

White-nose Syndrome Spreads

Photo: Michael Schirmacher

WNS has now been confirmed in 38 states and eight Canadian provinces, and researchers have found evidence of the fungus in five additional states including, most recently, Idaho and Colorado.

batsignals

Bridge leading to the core of the reserve.

Apply to be a BCI

Student Scholar

Photo: Taiye Adeyanju

Photo: Taiye Adeyanju

Team with the bike men hired at the Omo Bridge leading to the core of the reserve.

Apply to be a BCI Student Scholar

Graduate students can apply for funding through Oct. 31

Learn more and apply at batcon.org/student-scholars

Get Batty

Bat Week is Oct. 24–31

Planting agaves to celebrate Bat Week

Planting agaves to celebrate Bat Week

Learn more and get involved at batweek.org

Nimba Myotis

Binomial

Family

Colony size

Size

Diet

Status

ccording to Dr. Winifred Frick, Bat Conservation International’s (BCI’s) Chief Scientist, using harp traps to survey bat species is somewhat like trick-or-treating: You never know what you’re going to get.

Once the delicate nylon threads of the traps are installed near bat roosts, scientists wait to see which bats are caught. Dr. Frick says scientists are often like children comparing their hauls of Halloween candy. As they gently move the bats in small cloth bags to a nearby processing station where the bats are weighed and measured, DNA samples are collected, and varying species are noted, you might hear scientists quietly noting “one of these” and “three of those” before the bats are released into the night sky.

Preserving a Cave to Save the Jamaican Flower Bat

Right Photo: Sherri and Brock Fenton

n a Jamaican hill overlooking the ocean, new development is transforming the landscape. Gorgeous views and a COVID-era desire to get out of big cities like Kingston led to people snapping up countryside land and building homes. This area, in northeast Jamaica near the town of Port Antonio, is a very sought-after area for home building.

However, it is also the site of Stony Hill Cave, the only known maternity roost for the Critically Endangered Jamaican flower bat (Phyllonycteris aphylla).

Feature: Detection Dogs

Feature: Detection DogsData Dogs

usty deserved some positive reinforcement—approving words, tasty treats, and a scratch or two behind the ears. Blitz, too, has earned praise and recognition but prefers the reward of fetching a frisbee. These dogs—Dusty, an eight-year-old female Brittany, and Blitz, a five-year-old male red cattle dog—along with their human handler, Julia Nawrocki, are on a mission to collect meaningful data that, ultimately, may save migratory bats from fatal impacts with wind turbines.

Trekking into the Comoros

Dr. Mandl, a postdoctoral fellow funded by Bat Conservation International (BCI) at the University of Vienna in Austria, spent two months earlier this year on Anjouan, one of the islands of the Comoros, located between Madagascar and the coast of eastern Africa. Dr. Mandl was in search of a Critically Endangered Livingstone’s fruit bat (Pteropus livingstonii), a large black bat that has a population of around 1,200.

Bat Scientists Unite

bat scientist.

“It was a fantastic meeting and really special for everybody to be back together after three years,” says Bat Conservation International’s (BCI’s) Chief Scientist Dr. Winifred Frick. “The bat science community is an inclusive and tight community. NASBR has always been an annual event where people can come together to share research and support students.”

During the event, Dr. Frick received the Thomas H. Kunz Recognition Award for exemplary contributions by an early or mid-career bat scientist. Dr. Frick studied under Kunz, who passed away in 2020. He was her postdoctoral mentor and a key figure in the bat world.

Gardening for Bats

The “Guide to Gardening for Bats” provides helpful tips, ranging from the types of plants that attract the most nighttime pollinators to ideas on what to do with dead trees on your property.

Gardening tips

Erin Cord, BCI’s Community Engagement Manager, says this general guide is a way for people to learn how to make their yards friendlier for bats and wildlife. While there are more guides in development, such as ones that specify which types of plants are ideal for certain regions, Cord says that in general, light-colored blooms that attract nighttime pollinators are ideal for bats.

Drying Up

Like all animals, bats depend on water to survive—especially in arid or desert regions. Because they drink while in flight, bats must have open water sources like lakes, ponds, and springs, and in arid regions, they need to be able to drink at least once a night. In addition, the plants that grow around these water sources, called riparian vegetation, are the richest foraging habitat for insectivorous bats and several species rely on the trees that grow around water spots for roosting sites.

In other words, water loss is one of the significant drivers behind bat habitat loss, especially in regions that are already dry.

Researchers Remotely Peek Into the World of Bats

It wasn’t practical to send someone to sit outside each cave for weeks on end hoping to glimpse a bat. Instead, BLM and Bat Conservation International (BCI) partnered with Wildlife Imaging Systems (WIS), which created a system to automate the task and capture bat activity using cameras and infrared technology.

Through the Lens

ildlife photographer Chien Lee specializes in documenting the biological diversity of southeast Asia. Originally from California’s Bay Area, but based in northwest Borneo since 1996, he worked in environmental education and conservation before turning to photography full-time.

Bat Artist

fter she graduated from California State University, Monterey Bay (CSUMB), with a degree in marine science, Kristen Burroughs began working as a zookeeper. She worked in animal care and gave tours for several years, but she felt like she wanted to be more creative. So, she went back to school to earn a certificate in scientific illustration from CSUMB. As the final step in her program, she completed an internship with Bat Conservation International (BCI) during the summer of 2022.