Bat Conservation International Bats Magazine

Inside this Issue

Features

Horizonline Pictures

Departments

news & updates

- NASA’s Eclipse Soundscapes program

- Preventing pandemics

- Speaking up for bats at United Nations Convention of Migratory Species

- Leaf Shave helps boost bats

- Girl Scouts for bats

- Restoration with drones

- Advancing agave conservation

- White-nose Syndrome in Texas

- Protecting bats in Rwanda’s newest national park

- Miami Bat Lab at Zoo Miami

Image: Kristen Lear, Ph.D.

Growing a Global Movement to Save Bats

Our efforts to protect bats worldwide start with our expert Endangered Species Interventions team, which has been at the forefront of successful efforts to protect Nakanacagi Cave in Fiji, conserve Stony Hill Cave in Jamaica, and successfully deliver large-scale agave restoration for Endangered bats in the southwestern United States and northern Mexico. Recently, we brought on team members in Brazil and India to strengthen our work in those regions, as well as Africa, with new work in Kenya, Mozambique, and beyond.

Masthead

500 North Capital of Texas Highway, Building 1

Austin, TX 78746

512.327.9721

Kristen Pope

Javier Folgar

Michelle Donahue / Proofreader

Publication Management Unlock

Bats Magazine welcomes queries from writers. Send your article proposal in a brief outline form and a description of any photos, charts, or other graphics to the Editor at pubs@batcon.org.

Chair

Eileen Arbues,

Vice Chair

Ann George, Secretary

Dr. Gerald Carter

Gary Dreyzin

Danielle Gustafson

Cecily Longfield

Dr. Shahroukh Mistry

Sandy Read

Dr. Nancy Simmons

Jenn Stephens

Dr. Enrico Bernard

Dr. Sara Bumrungsri

Dr. Gerald Carter

Dr. Liliana Dávalos

Dr. Brock Fenton

Dr. Tigga Kingston

Dr. Stuart Parsons

Dr. Paul Racey

Dr. Danilo Russo

Dr. Nancy Simmons

Dr. Paul Webala

Mike Daulton, Executive Director

Mylea Bayless, Chief of Strategic Partnerships

Dr. Winifred Frick, Chief Scientist

Michael Nakamoto, Chief Operations Officer

Kevin Pierson, Chief of Conservation and Global Strategy

Bill Toomey, Chief Growth Officer

Visit BCI’s website at batcon.org and the following social media sites:

Total Eclipse of the Cave

Bat Signals

batsignals

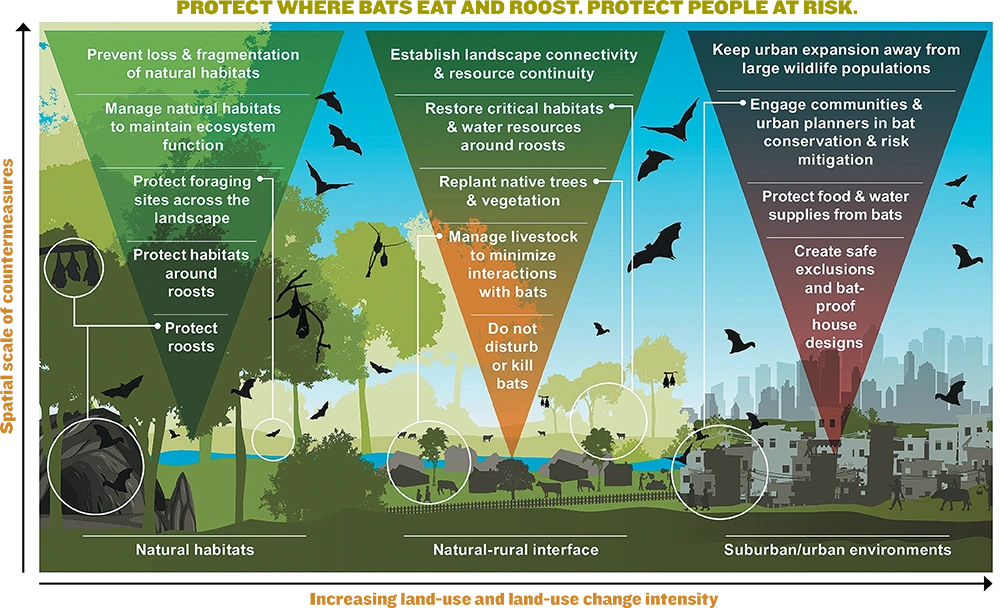

Ecological Countermeasures to Prevent Pandemics

The authors propose ecological intervention as the best strategy to prevent the next pandemic. They discuss how proactive policies, including integrated ecological approaches to be used alongside medical responses, are needed to develop a comprehensive pandemic prevention strategy.

Striped Leaf-Nosed Bat

Binomial

Family

Colony size

Weight

(180 grams)

Diet

Status

ew people have heard of the striped leaf-nosed bat (Macronycteris vittata). This large African bat is found in various populations across the continent, notably in larger colonies in Eastern and Southern Africa and smaller colonies in Western and Central Africa. While the striped leaf-nosed bat is an interesting species for many reasons, it needs to be better studied. Bat Conservation International (BCI) and partners are setting out to change that.

“Species-specific research on African bat species is so incredibly rare,” says Natalie Weber, a conservation scientist who works with BCI as Strategic Advisor for Endangered Species in Africa. “Unfortunately, the only efforts targeting this species were based on trying to find some viruses. But that’s not research on the species.”

On Location: Filming Bats Around the World

On Location: Filming Bats Around the World

n April, Melquisedec Gamba-Rios, Ph.D., and Jennifer Barros, Ph.D., placed small infrared lights in a tight tunnel-like passageway in Jamaica’s St. Clair Cave. Air temperatures outside the cave were approaching 90 degrees Fahrenheit, and humidity levels were very high. Inside, it was at least 10 degrees warmer—and wetter.

St. Clair Cave is one of the most important cave systems for bats in the Caribbean, with more than two million bats and 10 bat species, including the Critically Endangered Jamaican greater funnel-eared bats (Natalus jamaicensis). Gamba-Rios, Bat Conservation International (BCI)’s Regional Director in Latin America and the Caribbean, and Barros, BCI’s Brazil Program Manager, used infrared lights to minimize disturbing the bats and placed themselves near the bats’ exit. Soon, the bats began exiting the cave to scour the skies for insects, and look for fruit and nectar.

Collaboration for Conservation

n an April day in Chinchiná, Colombia, a group of bat conservationists put their acting skills to the test. Pretending to be an audience of schoolchildren, their roleplay helped Indonesian bat researcher Ellena Yusti refine a short improvised “elevator speech” explaining her work to a younger audience. Since bat conservationists must be able to communicate with everyone from kids to government officials to the general public, the exercise was a valuable chance to practice her skills in front of supportive colleagues. This was one of many memorable experiences during the inaugural workshop for the exciting new MENTOR-Bat program, a partnership between Bat Conservation International (BCI) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS).

Designed to promote long-term protection for bats and ecosystems by building capacity in key geographic regions, MENTOR-Bat brings together established and emerging bat conservationists from Colombia, Cameroon, and Indonesia in three cohorts, each consisting of one mentor and three fellows. Over 18 months, participants engage in virtual and in-person meetings, training opportunities, and workshops related to bat conservation and implementing bat conservation projects. The program also emphasizes One Health, focusing on protecting people and bats.

High-Flying Tools for Restoration

By soaring solo and nearly silently above the land, drones can save time and resources over a team of humans trekking out to gather data. They can also gather a greater volume and breadth of data than human scouts are able to discern with the naked eye without disrupting the environment on the ground. This light touch is especially valuable when it comes to projects taking place on already fragile land, like BCI’s restoration work in the Gila National Forest.

Beyond Borders

In early December 2023, the Northwest Mexico Agaves for Bats Summit convened in Hermosillo, Sonora, drawing representatives from 21 organizations. This gathering provided a platform for current and potential partners to exchange insights, discuss challenges, and explore avenues for collaboration on agave restoration and bat conservation. Among the attendees were organizations already profoundly engaged in BCI’s Agave Restoration Initiative and those eager to contribute to the initiative’s success.

White-Nose Syndrome

Pd was first detected in Texas in 2017. Texas has numerous cave systems and cave-hibernating bat species, such as cave myotis (Myotis velifer) and tricolored bats (Perimyotis subflavus), most vulnerable to WNS.

Sharing the Knowledge

Gishwati-Mukura is on a ridge that divides the watersheds of the Congo and the Nile rivers, more than a three-hour drive north of Nyungwe National Park. Unlike Rwanda’s three other national parks—Volcanoes National Park in the high central mountains of Rwanda, Akagera in the low-lying plains, and Nyungwe in the mountainous and oldest rainforest in Africa—Gishwati-Mukura is a conservation work in progress. The park was established less than 10 years ago to address several land use concerns, including illegal mining and livestock farming. Already, the restoration of the park’s indigenous hardwoods and bamboo, providing habitat for chimpanzees, monkeys, and hundreds of species of birds, is visibly apparent.

fieldnotes

Behind the Scenes with the Florida Bonneted Bat

Recently, a plan to develop a water park that would have impacted Florida bonneted bats and other species was reversed thanks to the hard work of avid conservationists, including BCI and partners, who expressed concerns about the location chosen for the water park. BCI, Zoo Miami, and partners are actively studying the remaining populations of Florida bonneted bats to understand their nightly foraging movements, roosting preferences, and diet. This information is necessary to protect the habitats they need to survive. The film production company Horizonline Pictures recently went to the field with the team to chronicle BCI’s work with this rare species. These are images from their time working with Florida bonneted bats.

Protecting Bats in India

ohit Chakravarty’s interest in wildlife dates back to his childhood in central India, the country’s tiger capital. As a boy, he was fascinated by tigers, and his focus gradually expanded to include birds and bats. Now based in Bangalore, Rohit has studied bats for over a decade and leads Bat Conservation International (BCI)’s India Endangered Species Initiative in partnership with a local organization, Nature Conservation Foundation.

How did you become interested in bats?

A Full-Circle Moment

hen embarking on a path of study, many people think they know which career path they would like to take. But, in many cases, the original path takes a completely new direction. That was certainly true for Shahroukh Mistry, Ph.D., who is now a professor of biology at Butte College in California and a member of Bat Conservation International (BCI)’s Board of Directors.

“I had never considered working on bats before I came to the United States for graduate studies,” Mistry says. “As a student in India, my passion was avian biology, and my first publication was on the nesting behavior of weaver birds.” However, as a graduate student at the University of Tennessee, Mistry joined his advisor, bat biologist Gary McCracken, Ph.D., for a summer research project in Texas.