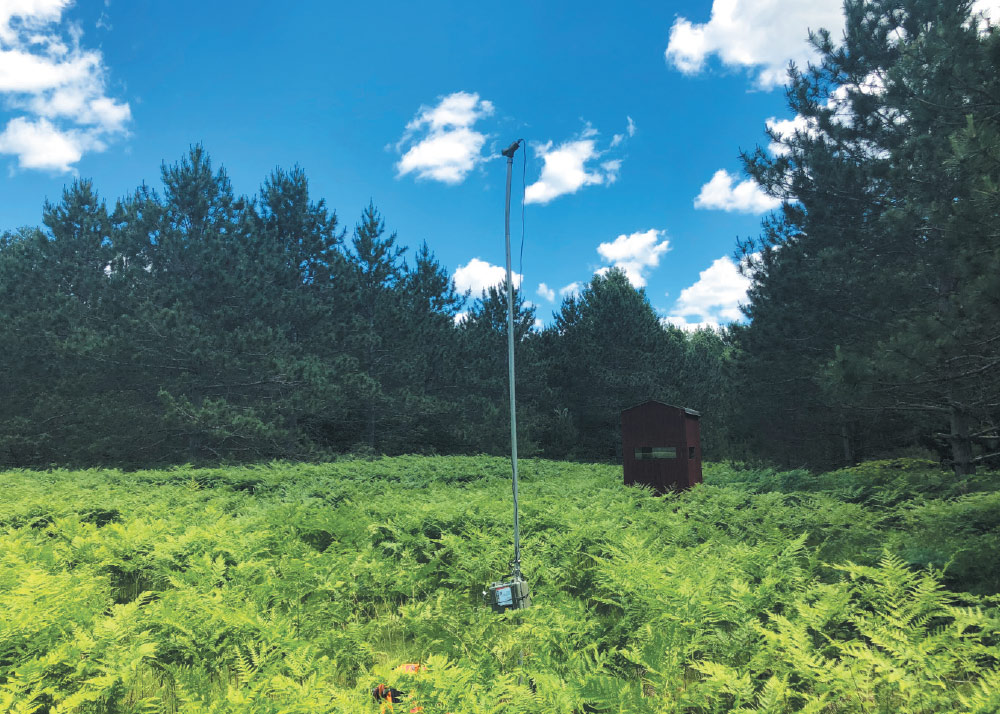

“To really understand what is going on at the local scale, we have to understand what’s going on at the regional and continental scale,” Loeb says, pointing out that the monitoring can help scientists piece together data in different locations to observe broader trends. “Several scientific papers have come out using NABat data that have shown that some species are really declining. We are able to show a continent- or partial continent-wide strong decline of these species.”

Data from NABat is also helping to inform decisions on energy development such as wind turbines. “A focus on migratory bats in NABat data is starting to help us understand their population trends,” Segers says. “How badly are they affected? Where are they affected? What are the variables that can help us predict whether and where these migratory bats are going to be most affected by wind energy so that it can ultimately inform government management decisions?”

Sharing data is a vital part of this effort, and NABat is helping researchers access a wide body of data, which can even help solve ecological mysteries.

“We’re constantly striving for open data sharing and creating community around getting information into people’s hands,” says Brian Reichert, NABat Program Coordinator at USGS. “We have status and trends for 14 different species currently, and we’re working on some new modeling approaches that will allow us to be able to estimate status and trends for the vast majority of the species that occur in the U.S. We’re also very close to finalizing some status and trends work for migratory tree bats, which has been an ongoing conversation for 20 years now.”

Migratory tree bats are a challenge to study, but NABat is a key element in gathering enough data to help researchers put all the puzzle pieces together.

“There’s been a lot of figurative head banging around how we get status and trends for migratory tree bats,” says Bethany Straw, NABat Assistant Program Coordinator and a USGS Biologist. “They present particular challenges because of their ecology and life history. We are now delivering on what has felt impossible for a decade or two.”

Feature: NABat

Feature: NABat