Mission 3

(Lasiurus cinereus)

Photo by Michael Durham / Minden Pictures

Averting a Collision Course

Hoary bats, eastern red bats (Lasisrus borealis), and silver-haired bats (Lasiurus noctivagans) are particularly vulnerable to colliding with the rotating blades of wind turbines. Without intervention, these bat species face alarming mortality rates as the wind energy industry grows, according to a scientific report co-authored by Dr. Winifred Frick, Chief Scientist for BCI, and Dr. Nick Friedenberg. The report, published in the journal Biological Conservation, models data on the population dynamics of hoary bats with projections that wind energy capacity will nearly double in the U.S. and Canada by 2030.

“The fatality rate of hoary bats at wind farms is alarming, and the potential risk to this species is of growing concern, especially as wind energy expands,” says Dr. Frick. But risks of massive decline and possible extinction can be reduced. For example, curtailment, angling the blades parallel to the wind to slow or stop them from turning during periods of high risk, reduces bat fatalities by an average of 62% while only slightly reducing annual energy production.

Since 2003, BCI’s Bats and Wind Energy Program has worked to find solutions that promote carbon-free energy production and prevent bat population declines.

Photo by Donald Solick

Mission 3

Photo by Donald Solick

Averting a Collision Course

Hoary bats, eastern red bats (Lasisrus borealis), and silver-haired bats (Lasiurus noctivagans) are particularly vulnerable to colliding with the rotating blades of wind turbines. Without intervention, these bat species face alarming mortality rates as the wind energy industry grows, according to a scientific report co-authored by Dr. Winifred Frick, Chief Scientist for BCI, and Dr. Nick Friedenberg. The report, published in the journal Biological Conservation, models data on the population dynamics of hoary bats with projections that wind energy capacity will nearly double in the U.S. and Canada by 2030.

“The fatality rate of hoary bats at wind farms is alarming, and the potential risk to this species is of growing concern, especially as wind energy expands,” says Dr. Frick. But risks of massive decline and possible extinction can be reduced. For example, curtailment, angling the blades parallel to the wind to slow or stop them from turning during periods of high risk, reduces bat fatalities by an average of 62% while only slightly reducing annual energy production.

Since 2003, BCI’s Bats and Wind Energy Program has worked to find solutions that promote carbon-free energy production and prevent bat population declines.

(Lasiurus cinereus)

Photo by Michael Durham / Minden Pictures

(Myotis septentrionalis)

Photo by J. Scott Altenbach

One Health: Examining Ecosystem Integrity

Photo by Heatherlee Leary

A Tightly Woven Tapestry

BCI collaborates closely with the North American Bat Monitoring Program (NABat) to monitor the health of bats and study the connection between ecosystem integrity and bat and human health.

Through this initiative, BCI obtains the information that is crucial for helping keep track of the status and trends of North American bat populations. BCI’s contribution to NABat’s expanding One Health approach included discovering numerous bat roosts across western North America.

Using various research tools, including volumes of acoustic recordings, BCI is coordinating the sampling and monitoring of data on bat health across eight states in the southern U.S., including Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas, Arizona, California, Nevada, and New Mexico.

Photo by Kristin Jonasson

The Forefront of White-nose Syndrome Research

BCI has been at the forefront of research in developing strategies to help conserve bats threatened by WNS. One promising solution BCI has been testing is to set up insect prey patches using UV light lures aimed at helping bats bulk up their fat reserves before winter hibernation. BCI has expanded testing by setting up bug buffets at 20 locations in nine states near winter roost sites of hibernating bats with WNS.

BCI is a leading collaborator with the North American Bat Monitoring Program (NABat) to assess hibernating bats’ population status and trends. BCI led a major collaborative effort to determine the population status and trends in northern long-eared bats, little brown bats, and tri-colored bats. Data was used to assess federal protections under the Endangered Species Act.

BCI works tirelessly to find solutions for bats imperiled by WNS—working on strategies in areas where remnant bat colonies are surviving to test approaches at the disease frontier in Texas.

The Forefront of White-nose Syndrome Research

BCI has been at the forefront of research in developing strategies to help conserve bats threatened by WNS. One promising solution BCI has been testing is to set up insect prey patches using UV light lures aimed at helping bats bulk up their fat reserves before winter hibernation. BCI has expanded testing by setting up bug buffets at 20 locations in nine states near winter roost sites of hibernating bats with WNS.

BCI is a leading collaborator with the North American Bat Monitoring Program (NABat) to assess hibernating bats’ population status and trends. BCI led a major collaborative effort to determine the population status and trends in northern long-eared bats, little brown bats, and tri-colored bats. Data was used to assess federal protections under the Endangered Species Act.

BCI works tirelessly to find solutions for bats imperiled by WNS—working on strategies in areas where remnant bat colonies are surviving to test approaches at the disease frontier in Texas.

(Myotis septentrionalis)

Photo by J. Scott Altenbach

Photo by Kristin Jonasson

One Health: Examining Ecosystem Integrity

A Tightly Woven Tapestry

BCI collaborates closely with the North American Bat Monitoring Program (NABat) to monitor the health of bats and study the connection between ecosystem integrity and bat and human health.

Through this initiative, BCI obtains the information that is crucial for helping keep track of the status and trends of North American bat populations. BCI’s contribution to NABat’s expanding One Health approach included discovering numerous bat roosts across western North America.

Using various research tools, including volumes of acoustic recordings, BCI is coordinating the sampling and monitoring of data on bat health across eight states in the southern U.S., including Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas, Arizona, California, Nevada, and New Mexico.

Photo by Heatherlee Leary

516

surveyed sites

2,427,940

acoustic recordings processed and submitted to NABat

Leading Partnerships

Conducting Sound Science

BCI is a leading partner in NABat, an international collaboration with more than 160 groups contributing data for the purposes of bat conservation. NABat includes numerous U.S. and Canadian government agencies, academic institutions, and nonprofit organizations. Our team provides leadership to the NABat program and is continually innovating with NABat partners to enhance data collection and processing and to provide the most comprehensive effort to measure and monitor the status and trends of bats across the continent.

In 2022, BCI’s leadership in NABat was pivotal in:

- Launching two new coordination hubs for advancing bat research and monitoring in the Pacific and Southwest U.S.

- Improving quantitative solutions in reporting on at-risk bat species

- Growing stakeholder participation and increasing data contributions to further collaboration on programmatic priorities

- Recording echolocation calls from different species to help improve AI approaches to identifying bats by their echolocation signals

- Expanding the NABat program to monitor bat health as part of a One Health initiative

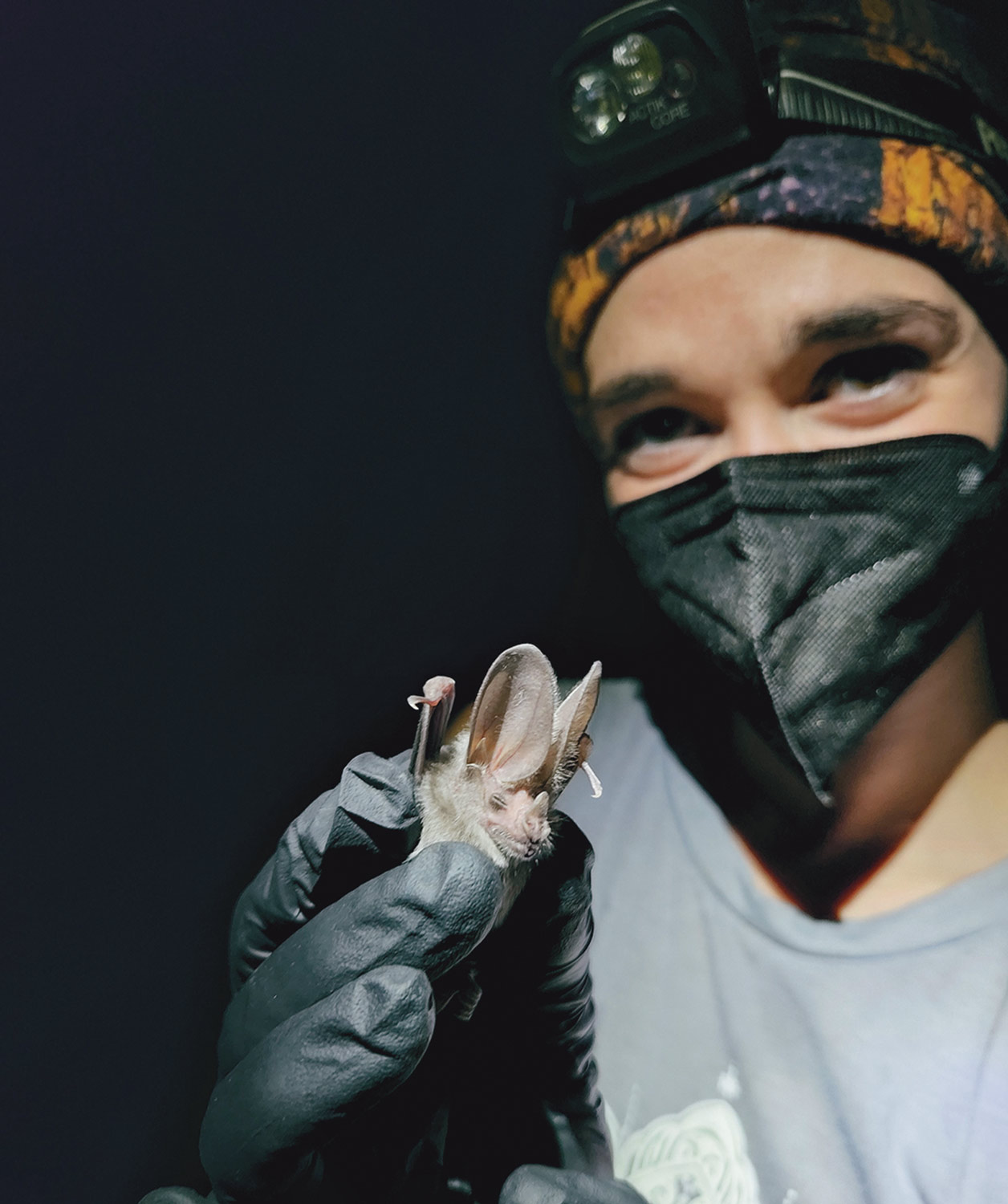

BCI Scholar María Elena Torres Ruiz Díaz monitors bats in two green areas of the Metropolitan Area of Asunción, Paraguay.

Student Scholars:

The Future of Bat Conservation

BCI’s ongoing Student Scholar Program recognizes emerging graduate researchers around the world for their potential to significantly contribute to global bat conservation.

In 2022, BCI supported 13 researchers, and their projects in 12 countries: Brazil, Ecuador, Ghana, Equatorial Guinea, India, Kenya, Madagascar, Nepal, Nigeria, Paraguay, South Africa, and the U.S. Projects ranged from inventorying bat species in a region of rich biological resources in the Eastern Indian Himalayas to studying the roosting patterns of cave-dwelling bats in Nepal to analyzing the impacts of light pollution on bat species in the U.S.

“BCI’s Student Scholar Program helps build location-specific knowledge about bat species around the world—knowledge that is shareable and often adaptable in other locations,” says Dr. Amanda Adams, BCI’s Conservation Research Program Manager. “Moreover, the program unites a global community of bat researchers.”

+ Brazil

+ Ecuador

+ Ghana

+ Equatorial Guinea

+ India

+ Kenya

+ Madagascar

+ Nepal

+ Nigeria

+ Paraguay

+ South Africa

+ United States

BCI Scholar María Elena Torres Ruiz Díaz monitors bats in two green areas of the Metropolitan Area of Asunción, Paraguay.